Introduction¶

This document will introduce you to Singularity, If you are viewing this on the web there should be links in the bar to the left that will direct you to other important topics. If you want to get a quick overview, see our quickstart. If you want to understand which commands are a best fit for your use case, see our build flow section. There is also a separate Singularity Administration Guide that targets system administrators, so if you are a service provider, or an interested user, it is encouraged that you read that document as well.

Welcome to Singularity!¶

Singularity is a container solution created by necessity for scientific and application driven workloads. Over the past decade and a half, virtualization has gone from an engineering toy to a global infrastructure necessity and the evolution of enabling technologies has flourished. Most recently, we have seen the introduction of the latest spin on virtualization… “containers”. People tend to view containers in light of their virtual machine ancestry and these preconceptions influence feature sets and expected use cases. This is both a good and a bad thing… For industry and enterprise-centric container technologies this is a good thing. Web enabled cloud requirements are very much in alignment with the feature set of virtual machines, and thus the preceding container technologies. But the idea of containers as miniature virtual machines is a bad thing for the scientific world and specifically the high performance computation (HPC) community. While there are many overlapping requirements in these two fields, they differ in ways that make a shared implementation generally incompatible. Some groups have leveraged custom-built resources that can operate on a lower performance scale, but proper integration is difficult and perhaps impossible with today’s technology. Many scientists could benefit greatly by using container technology, but they need a feature set that differs somewhat from that available with current container technology. This necessity drives the creation of Singularity and articulated its four primary functions:

Mobility of Compute¶

Mobility of compute is defined as the ability to define, create and

maintain a workflow and be confident that the workflow can be executed

on different hosts, operating systems (as long as it is Linux) and

service providers. Being able to contain the entire software stack,

from data files to library stack, and portably move it from system to

system means true mobility.

Singularity achieves this by utilizing a distributable image format

that contains the entire container and stack into a single file. This

file can be copied, shared, archived, and standard UNIX file

permissions also apply. Additionally containers are portable (even

across different C library versions and implementations) which makes

sharing and copying an image as easy as cp or scp or ftp.

Reproducibility¶

As mentioned above, Singularity containers utilize a single file which is the complete representation of all the files within the container. The same features which facilitate mobility also facilitate reproducibility. Once a contained workflow has been defined, a snapshot image can be taken of a container. The image can be then archived and locked down such that it can be used later and you can be confident that the code within the container has not changed.

User Freedom¶

System integrators, administrators, and engineers spend a lot of effort maintaining their systems, and tend to take a cautious approach. As a result, it is common to see hosts installed with production, mission critical operating systems that are “old” and have few installed packages. Users may find software or libraries that are too old or incompatible with the software they must run, or the environment may just lack the software stack they need due to complexities with building, specific software knowledge, incompatibilities or conflicts with other installed programs.

Singularity can give the user the freedom they need to install the applications, versions, and dependencies for their workflows without impacting the system in any way. Users can define their own working environment and literally copy that environment image (single file) to a shared resource, and run their workflow inside that image.

Support on Existing Traditional HPC¶

Replicating a virtual machine cloud like environment within an existing HPC resource is not a reasonable goal for many administrators. There are a lots of container systems available which are designed for enterprise, as a replacement for virtual machines, are cloud focused, or require unstable or unavailable kernel features. Singularity supports existing and traditional HPC resources as easily as installing a single package onto the host operating system. Custom configurations may be achieved via a single configuration file, and the defaults are tuned to be generally applicable for shared environments. Singularity can run on host Linux distributions from RHEL6 (RHEL5 for versions lower than 2.2) and similar vintages, and the contained images have been tested as far back as Linux 2.2 (approximately 14 years old). Singularity natively supports InfiniBand, Lustre, and works seamlessly with all resource managers (e.g. SLURM, Torque, SGE, etc.) because it works like running any other command on the system. It also has built-in support for MPI and for containers that need to leverage GPU resources.

A High Level View of Singularity¶

Security and privilege escalation¶

A user inside a Singularity container is the same user as outside the container This is one of Singularities defining characteristics. It allows a user (that may already have shell access to a particular host) to simply run a command inside of a container image as themselves. The following example scenario will help illustrate a Singularity container:

%SERVER and %CLUSTER are large expensive systems with resources far exceeding those of my personal workstation. But because they are shared systems, no users have root access. The environments are tightly controlled and managed by a staff of system administrators. To keep these systems secure, only the system administrators are granted root access and they control the state of the operating systems and installed applications. If a user is able to escalate to root (even within a container) on %SERVER or %CLUSTER, they can do bad things to the network, cause denial of service to the host (as well as other hosts on the same network), and may have unrestricted access to file systems reachable by the container.

To mitigate security concerns like this, Singularity limits one’s ability to escalate permission inside a container. For example, if I do not have root access on the target system, I should not be able to escalate my privileges within the container to root either. This is semi-antagonistic to Singularity’s 3rd tenant; allowing the users to have freedom of their own environments. Because if a user has the freedom to create and manipulate their own container environment, surely they know how to escalate their privileges to root within that container. Possible means to escalation could include setting the root user’s password, or enabling themselves to have sudo access. For these reasons, Singularity prevents user context escalation within the container, and thus makes it possible to run user supplied containers on shared infrastructures. This mitigation dictates the Singularity workflow. If a user needs to be root in order to make changes to their containers, then they need to have an endpoint (a local workstation, laptop, or server) where they have root access. Considering almost everybody at least has a laptop, this is not an unreasonable or unmanageable mitigation, but it must be defined and articulated.

The Singularity container image¶

Singularity makes use of a container image file, which physically includes the container. This file is a physical representation of the container environment itself. If you obtain an interactive shell within a Singularity container, you are literally running within that file. This design simplifies management of files to the element of least surprise, basic file permission. If you either own a container image, or have read access to that container image, you can start a shell inside that image. If you wish to disable or limit access to a shared image, you simply change the permission ACLs to that file. There are numerous benefits for using a single file image for the entire container:

Copying or branching an entire container is as simple as

cpPermission/access to the container is managed via standard file system permissions

Large scale performance (especially over parallel file systems) is very efficient

No caching of the image contents to run (especially nice on clusters)

Containers are compressed and consume very little disk space

Images can serve as stand-alone programs, and can be executed like any other program on the host

Copying, sharing, branching, and distributing your image¶

A primary goal of Singularity is mobility. The single file image format makes mobility easy. Because Singularity images are single files, they are easily copied and managed. You can copy the image to create a branch, share the image and distribute the image as easily as copying any other file you control!

If you want an automated solution for building and hosting your image, you can use our container registry Singularity Hub. Singularity Hub can automatically build Singularity recipe files from a GitHub repository each time that you push. It provides a simple cloud solution for storing and sharing your image. If you want to host your own Registry, then you should check out Singularity Registry. If you have ideas or suggestions for how Singularity can better support reproducible science, please reach out!.

Supported container formats¶

squashfs: the default container format is a compressed read-only file system that is widely used for things like live CDs/USBs and cell phone OS’s

ext3: (also called

writable) a writable image file containing an ext3 file system that was the default container format prior to Singularity version 2.4directory: (also called

sandbox) standard Unix directory containing a root container imagetar.gz: zlib compressed tar archive

tar.bz2: bzip2 compressed tar archive

tar: uncompressed tar archive

Supported Uniform Resource Identifiers (URI)¶

Singularity also supports several different mechanisms for obtaining the images using a standard URI format.

shub:// Singularity Hub is our own registry for Singularity containers. If you want to publish a container, or give easy access to others from their command line, or enable automatic builds, you should build it on Singularity Hub.

docker:// Singularity can pull Docker images from a Docker registry, and will run them non-persistently (e.g. changes are not persisted as they can not be saved upstream). Note that pulling a Docker image implies assembling layers at runtime, and two subsequent pulls are not guaranteed to produce an identical image.

instance:// A Singularity container running as service, called an instance, can be referenced with this URI.

Name-spaces and isolation¶

When asked, “What namespaces does Singularity virtualize?”, the most appropriate response from a Singularity point of view is “As few as possible!”. This is because the goals of Singularity are mobility, reproducibility and freedom, not full isolation (as you would expect from industry driven container technologies). Singularity only separates the needed namespaces in order to satisfy our primary goals.

Coupling incomplete isolation with the fact that a user inside a container is the same user outside the container, allows Singularity to blur the lines between a container and the underlying host system. Using Singularity feels like running in a parallel universe, where there are two time lines. In one time line, the system administrators installed their operating system of choice. But on an alternate time line, we bribed the system administrators and they installed our favorite operating system and apps, and gave us full control but configured the rest of the system identically. And Singularity gives us the power to pick between these two time lines. In other words, Singularity allows you to virtually swap out the underlying operating system for one that you’ve defined without affecting anything else on the system and still having all of the host resources available to you.

The container is similar to logging into another identical host running a different operating system. e.g. One moment you are on Centos-6 and the next minute you are on the latest version of Ubuntu that has Tensorflow installed, or Debian with the latest OpenFoam, or a custom workflow that you installed. But you are still the same user with the same files running the same PIDs. Additionally, the selection of name-space virtualization can be dynamic or conditional. For example, the PID namespace is not separated from the host by default, but if you want to separate it, you can with a command line (or environment variable) setting. You can also decide if you want to contain a process so it can not reach out to the host file system if you don’t know if you trust the image. But by default, you are allowed to interface with all of the resources, devices and network inside the container as you are outside the container (given your level of permissions).

Compatibility with standard work-flows, pipes and IO¶

Singularity abstracts the complications of running an application in an environment that differs from the host. For example, applications or scripts within a Singularity container can easily be part of a pipeline that is being executed on the host. Singularity containers can also be executed from a batch script or other program (e.g. an HPC system’s resource manager) natively. Some usage examples of Singularity can be seen as follows:

$ singularity exec dummy.img xterm # run xterm from within the container

$ singularity exec dummy.img python script.py # run a script on the host system using container's python

$ singularity exec dummy.img python < /path/to/python/script.py # do the same via redirection

$ cat /path/to/python/script.py | singularity exec dummy.img python # do the same via a pipe

You can even run MPI executables within the container as simply as:

$ mpirun -np X singularity exec /path/to/container.img /usr/bin/mpi_program_inside_container (mpi program args)

The Singularity Process Flow¶

When executing container commands, the Singularity process flow can be generalized as follows:

Singularity application is invoked

Global options are parsed and activated

The Singularity command (subcommand) process is activated

Subcommand options are parsed

The appropriate sanity checks are made

Environment variables are set

The Singularity Execution binary is called (

sexec)Sexec determines if it is running privileged and calls the

SUIDcode if necessaryNamespaces are created depending on configuration and process requirements

The Singularity image is checked, parsed, and mounted in the namespace

Bind mount points are setup so that files on the host are visible in the

CLONE_NEWNScontainerThe namespace

CLONE_FSis used to virtualize a new root file systemSingularity calls

execvp()and Singularity process itself is replaced by the process inside the containerWhen the process inside the container exits, all namespaces collapse with that process, leaving a clean system

All of the above steps are fast and seem instantaneous to the user (i.e. there is little run-time overhead), when measured on a standard server the overhead was approximately 15-25 thousandths of a second).

The Singularity Usage Workflow¶

The security model of Singularity (as described above, “A user inside a Singularity container is the same user as outside the container”) defines the Singularity workflow. There are generally two groups of actions you must implement on a container; management (building your container) and usage.

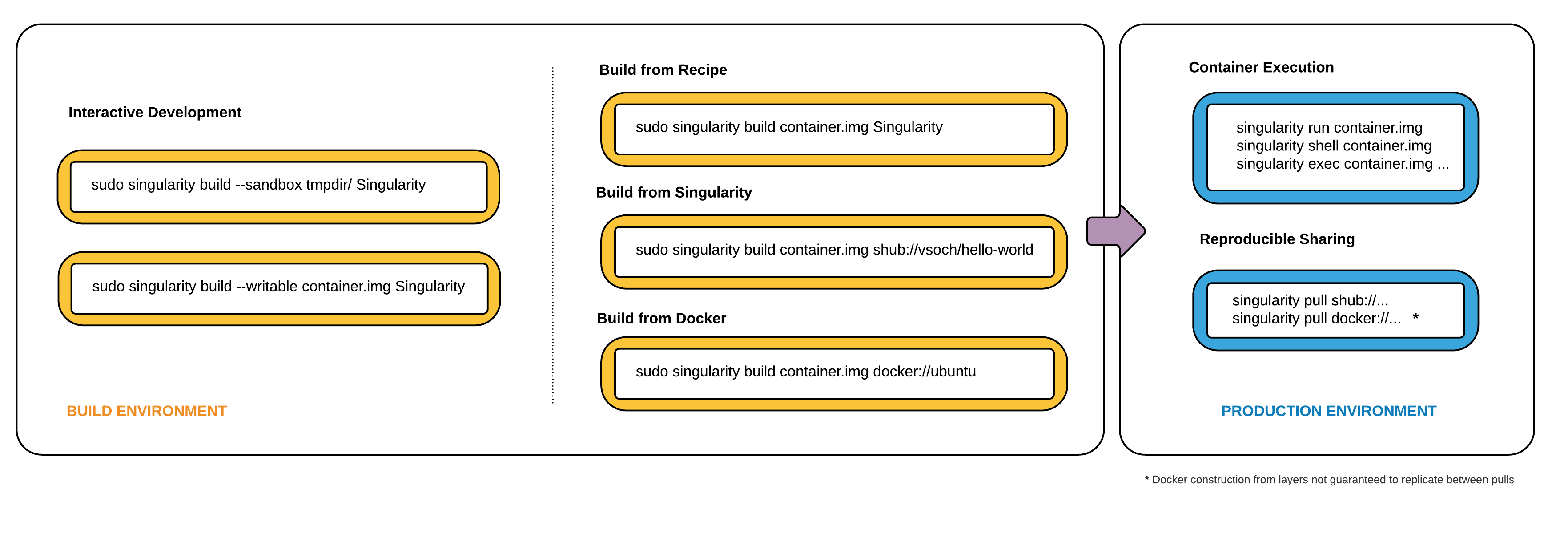

In many circumstances building containers require root administrative privileges just like these actions would require on any system, container, or virtual machine. This means that a user must have access to a system on which they have root privileges. This could be a server, workstation, a laptop, virtual machine, or even a cloud instance. If you are using OS X or Windows on your laptop, it is recommended to setup Vagrant, and run Singularity from there (there are recipes for this which can be found at the Singularity website. Once you have Singularity installed on your endpoint of choice, this is where you will do the bulk of your container development. This workflow can be described visually as follows:

Singularity workflow¶

On the left side, you have your build environment: a laptop, workstation, or a server that you control. Here you will (optionally):

develop and test containers using

--sandbox(build into a writable directory) or--writable(build into a writable ext3 image)build your production containers with a squashfs filesystem.

Once you have the container with the necessary applications, libraries and data inside it can be easily shared to other hosts and executed without requiring root access. A production container should be an immutable object, so if you need to make changes to your container you should go back to your build system with root privileges, rebuild the container with the necessary changes, and then re-upload the container to the production system where you wish to run it.

Singularity Commands¶

How do the commands work?

The following is a list of the Singularity commands, Click on each command for more information.

build : Build a container on your user endpoint or build environment

exec : Execute a command to your container

inspect : See labels, run and test scripts, and environment variables

pull : pull an image from Docker or Singularity Hub

run : Run your image as an executable

shell : Shell into your image

Image Commands

image.import : import layers or other file content to your image

image.export : export the contents of the image to tar or stream

image.create : create a new image, using the old ext3 filesystem

image.expand : increase the size of your image (old ext3)

instances : Start, stop, and list container instances

Deprecated Commands The following commands are deprecated in 2.4 and will be removed in future releases.

bootstrap : Bootstrap a container recipe

Support¶

Have a question, or need further information? Reach out to us.

About¶

Overview¶

While there are many container solutions being used commonly in this day and age, what makes Singularity different stems from it’s primary design features and thus it’s architecture:

Reproducible software stacks: These must be easily verifiable via checksum or cryptographic signature in such a manner that does not change formats (e.g. splatting a tarball out to disk). By default Singularity uses a container image file which can be checksummed, signed, and thus easily verified and/or validated.

Mobility of compute: Singularity must be able to transfer (and store) containers in a manner that works with standard data mobility tools (rsync, scp, gridftp, http, NFS, etc..) and maintain software and data controls compliancy (e.g. HIPAA, nuclear, export, classified, etc..)

Compatibility with complicated architectures: The runtime must be immediately compatible with existing HPC, scientific, compute farm and even enterprise architectures any of which maybe running legacy kernel versions (including RHEL6 vintage systems) which do not support advanced namespace features (e.g. the user namespace)

Security model: Unlike many other container systems designed to support trusted users running trusted containers we must support the opposite model of untrusted users running untrusted containers. This changes the security paradigm considerably and increases the breadth of use cases we can support.

Background¶

A Unix operating system is broken into two primary components, the kernel space, and the user space. The Kernel supports the user space by interfacing with the hardware, providing core system features and creating the software compatibility layers for the user space. The user space on the other hand is the environment that most people are most familiar with interfacing with. It is where applications, libraries and system services run.

Containers are shifting the emphasis away from the runtime environment by commoditizing the user space into swappable components. This means that the entire user space portion of a Linux operating system, including programs, custom configurations, and environment can be interchanged at runtime. Singularity emphasis and simplifies the distribution vector of containers to be that of a single, verifiable file.

Software developers can now build their stack onto whatever operating system base fits their needs best, and create distributable runtime encapsulated environments and the users never have to worry about dependencies, requirements, or anything else from the user space.

Singularity provides the functionality of a virtual machine, without the heavyweight implementation and performance costs of emulation and redundancy!

The Singularity Solution¶

Singularity has two primary roles:

Container Image Generator: Singularity supports building different container image formats from scratch using your choice of Linux distribution bases or leveraging other container formats (e.g. Docker Hub). Container formats supported are the default compressed immutable (read only) image files, writable raw file system based images, and sandboxes (chroot style directories).

Container Runtime: The Singularity runtime is designed to leverage the above mentioned container formats and support the concept of untrusted users running untrusted containers. This counters the typical container runtime practice of trusted users running trusted containers and as a result of that, Singularity utilizes a very different security paradigm. This is a required feature for implementation within any multi-user environment.

The Singularity containers themselves are purpose built and can include a simple application and library stack or a complicated work flow that can interface with the hosts resources directly or run isolated from the host and other containers. You can even launch a contained work flow by executing the image file directly! For example, assuming that ~/bin is in the user’s path as it is normally by default:

$ mkdir ~/bin

$ singularity build ~/bin/python-latest docker://python:latest

Docker image path: index.docker.io/library/python:latest

Cache folder set to /home/gmk/.singularity/docker

Importing: base Singularity environment

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:aa18ad1a0d334d80981104c599fa8cef9264552a265b1197af11274beba767cf.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:15a33158a1367c7c4103c89ae66e8f4fdec4ada6a39d4648cf254b32296d6668.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:f67323742a64d3540e24632f6d77dfb02e72301c00d1e9a3c28e0ef15478fff9.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:c4b45e832c38de44fbab83d5fcf9cbf66d069a51e6462d89ccc050051f25926d.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:b71152c33fd217d4408c0e7a2f308e66c0be1a58f4af9069be66b8e97f7534d2.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:c3eac66dc8f6ae3983a7f37e3da84a8acb828faf909be2d6649e9d7c9caffc28.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:494ffdf1660cdec946ae13d6b726debbcec4c393a7eecfabe97caf3961f62c36.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/docker/sha256:f5ec737c23de3b1ae2b1ce3dce1fd20e0cb246e4c73584dcd4f9d2f50063324e.tar.gz

Importing: /home/gmk/.singularity/metadata/sha256:5dd22488ce22f06bed1042cc03d3efa5a7d68f2a7b3dcad559df4520154ef9c2.tar.gz

WARNING: Building container as an unprivileged user. If you run this container as root

WARNING: it may be missing some functionality.

Building Singularity image...

Cleaning up...

Singularity container built: /home/gmk/bin/python-latest

$ which python-latest

/home/gmk/bin/python-latest

$ python-latest --version

Python 3.6.3

$ singularity exec ~/bin/python-latest cat /etc/debian_version

8.9

$ singularity shell ~/bin/python-latest

Singularity: Invoking an interactive shell within container...

Singularity python-latest:~>

Additionally, Singularity blocks privilege escalation within the container and you are always yourself within a container! If you want to be root inside the container, you first must be root outside the container. This simple usage paradigm mitigates many of the security concerns that exists with containers on multi-user shared resources. You can directly call programs inside the container from outside the container fully incorporating pipes, standard IO, file system access, X11, and MPI. Singularity images can be seamlessly incorporated into your environment.

Portability and Reproducibility¶

Singularity containers are designed to be as portable as possible, spanning many flavors and vintages of Linux. The only known limitation is binary compatibility of the kernel and container. Singularity has been ported to distributions going as far back as RHEL 5 (and compatibles) and works on all currently living versions of RHEL, Debian, Arch, Alpine, Gentoo and Slackware. Within the container, there are almost no limitations aside from basic binary compatibility.

Inside the container, it is also possible to have a very old version of Linux supported. The oldest known version of Linux tested was a Red Hat Linux 8 container, that was converted by hand from a physical computer’s hard drive as the 15 year old hardware was failing. The container was transferred to a new installation of Centos7, and is still running in production!

Each Singularity image includes all of the application’s necessary run-time libraries and can even include the required data and files for a particular application to run. This encapsulation of the entire user-space environment facilitates not only portability but also reproducibility.

Features¶

Encapsulation of the environment¶

Mobility of Compute is the encapsulation of an environment in such a manner to make it portable between systems. This operating system environment can contain the necessary applications for a particular work-flow, development tools, and/or raw data. Once this environment has been developed it can be easily copied and run from any other Linux system.

This allows users to BYOE (Bring Their Own Environment) and work within that environment anywhere that Singularity is installed. From a service provider’s perspective we can easily allow users the flexibility of “cloud”-like environments enabling custom requirements and workflows.

Additionally there is always a misalignment between development and production environments. The service provider can only offer a stable, secure tuned production environment which in many times will not keep up with the fast paced requirements of developers. With Singularity, you can control your own development environment and simply copy them to the production resources.

Containers are image based¶

Using image files have several key benefits:

First, this image serves as a vector for mobility while retaining permissions of the files within the image. For example, a user may own the image file so they can copy the image to and from system to system. But, files within an image must be owned by the appropriate user. For example, ‘/etc/passwd’ and ‘/’ must be owned by root to achieve appropriate access permission. These permissions are maintained within a user owned image.

There is never a need to build, rebuild, or cache an image! All IO happens on an as needed basis. The overhead in starting a container is in the thousandths of a second because there is never a need to pull, build or cache anything!

On HPC systems a single image file optimizes the benefits of a shared parallel file system! There is a single metadata lookup for the image itself, and the subsequent IO is all directed to the storage servers themselves. Compare this to the massive amount of metadata IO that would be required if the container’s root file system was in a directory structure. It is not uncommon for large Python jobs to DDOS (distributed denial of service) a parallel meta-data server for minutes! The Singularity image mitigates this considerably.

No user contextual changes or root escalation allowed¶

When Singularity is executed, the calling user is maintained within the container. For example, if user ‘gmk’ starts a Singularity container, the same user ‘gmk’ will end up within the container. If ‘root’ starts the container, ‘root’ will be the user inside the container.

Singularity also limits a user’s ability to escalate privileges within the container. Even if the user works in their own environment where they configured ‘sudo’ or even removed root’s password, they will not be able to ‘sudo’ or ‘su’ to root. If you want to be root inside the container, you must first be root outside the container.

Because of this model, it becomes possible to blur the line of access between what is contained and what is on the host as Singularity does not grant the user any more access than they already have. It also enables the implementation on shared/multi-tenant resources.

No root owned daemon processes¶

Singularity does not utilize a daemon process to manage the containers. While daemon processes do facilitate certain types of workflows and privilege escalation, it breaks all resource controlled environments. This is because a user’s job becomes a subprocess of the daemon (rather than the user’s shell) and the daemon process is outside of the reach of a resource manager or batch scheduler.

Additionally, securing a root owned daemon process which is designed to manipulate the host’s environment becomes tricky. In currently implemented models, it is possible to grant permissions to users to control the daemon, or not. There is no sense of ACL’s or access of what users can and can not do.

While there are some other container implementations that do not leverage a daemon, they lack other features necessary to be considered as reasonable user facing solution without having root access. For example, there has been a standing unimplemented patch to RunC (already daemon-less) which allows for root-less usage (no root). But, user contexts are not maintained, and it will only work with chroot directories (instead of an image) where files must be owned and manipulated by the root user!

Use Cases¶

BYOE: Bring Your Own Environment¶

Engineering work-flows for research computing can be a complicated and iterative process, and even more so on a shared and somewhat inflexible production environment. Singularity solves this problem by making the environment flexible.

Additionally, it is common (especially in education) for schools to provide a standardized pre-configured Linux distribution to the students which includes all of the necessary tools, programs, and configurations so they can immediately follow along.

Reproducible science¶

Singularity containers can be built to include all of the programs, libraries, data and scripts such that an entire demonstration can be contained and either archived or distributed for others to replicate no matter what version of Linux they are presently running.

Commercially supported code requiring a particular environment Some commercial applications are only certified to run on particular versions of Linux. If that application was installed into a Singularity container running the version of Linux that it is certified for, that container could run on any Linux host. The application environment, libraries, and certified stack would all continue to run exactly as it is intended.

Additionally, Singularity blurs the line between container and host such that your home directory (and other directories) exist within the container. Applications within the container have full and direct access to all files you own thus you can easily incorporate the contained commercial application into your work and process flow on the host.

Static environments (software appliances)¶

Fund once, update never software development model. While this is not ideal, it is a common scenario for research funding. A certain amount of money is granted for initial development, and once that has been done the interns, grad students, post-docs, or developers are reassigned to other projects. This leaves the software stack un-maintained, and even rebuilds for updated compilers or Linux distributions can not be done without unfunded effort.

Legacy code on old operating systems¶

Similar to the above example, while this is less than ideal it is a fact of the research ecosystem. As an example, I know of one Linux distribution which has been end of life for 15 years which is still in production due to the software stack which is custom built for this environment. Singularity has no problem running that operating system and application stack on a current operating system and hardware.

Complicated software stacks that are very host specific¶

There are various software packages which are so complicated that it takes much effort in order to port, update and qualify to new operating systems or compilers. The atmospheric and weather applications are a good example of this. Porting them to a contained operating system will prolong the use-fullness of the development effort considerably.

Complicated work-flows that require custom installation and/or data¶

Consolidating a work-flow into a Singularity container simplifies distribution and replication of scientific results. Making containers available along with published work enables other scientists to build upon (and verify) previous scientific work.

License¶

Singularity is released under a standard 3 clause BSD license. Please see our LICENSE file for more details).

Getting started¶

Jump in and get started, or find ways to get help.

Project lead: Gregory M. Kurtzer